In 1998, I was working for Production Designer Bill Malley on a television show called Seven Days. The premise of the show was that the government had designed a time machine that could go back in time exactly seven days from the present and decided they could use it to “undo” or “back-step” major global political disasters.

The fictional location of the Time Machine was in a site in the Nevada desert called “Never Never Land”, a play on Area 51.

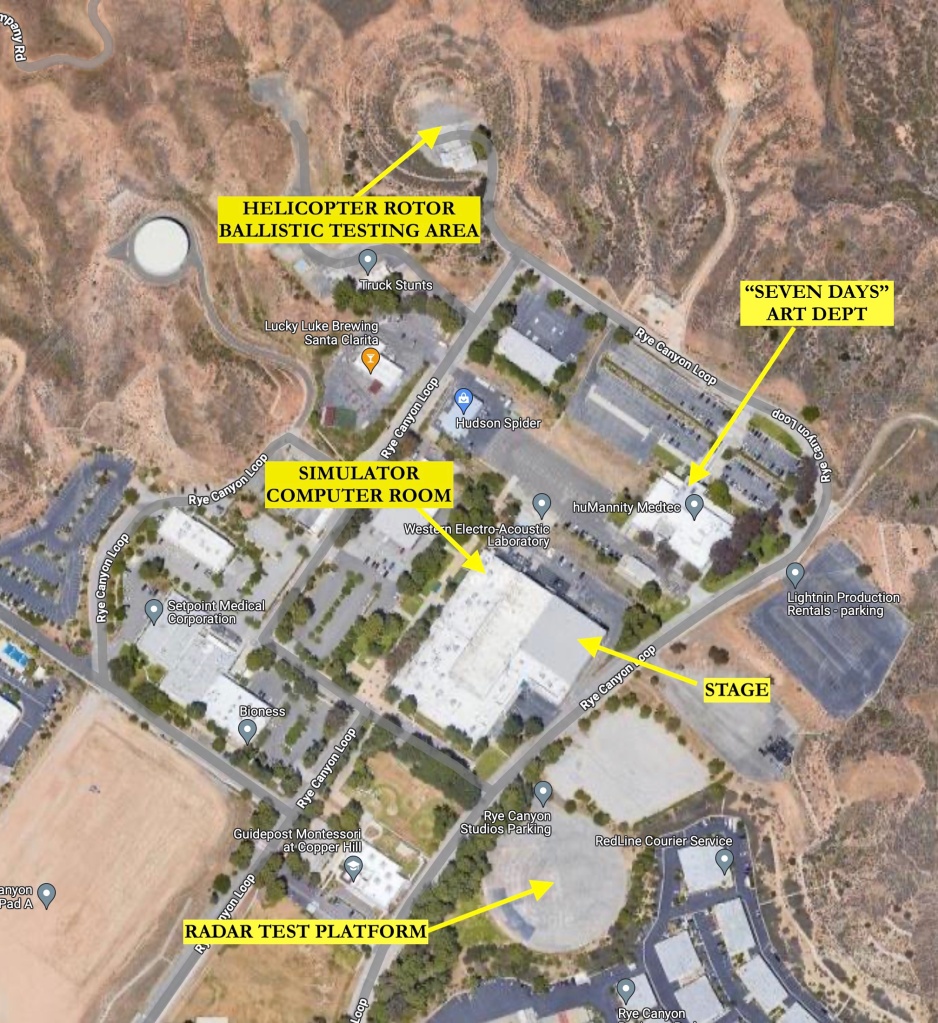

The irony of the shooting location, which no one has ever mentioned, is that we were the first production to shoot on the site of what was once the top secret weapons testing site of Lockheed Skunkworks in Burbank, California. But this site, the former Rye Canyon Weapons Testing site, was far from Burbank. Situated out in Santa Clarita, it was just across the road from the Six Flags Magic Mountain Amusement Park.

Before the park was there, and before Santa Clarita began to expand, the area was a remote location nestled in the hills where the Lockheed employees could work in relative obscurity. The site was, according to the remaining employees, so heavily populated with deer that one was bagged each 4th of July for the company barbecue.

There were still remnants of the original facility, including a building with an anechoic chamber where sound tests were done. One day they wheeled an old refrigerator into the room and with the flick of a switch, emitted a sound wave that blew the enamel completely off the metal of the appliance.

At the south end of the lot was a strange circular concrete pad that I would only later learn the purpose for.

The Art Department and production office were set up in a modern building to the north end of the facility. It was a “quiet building”, especially built for Lockheed. The only windows were on the exterior walls. The inner chamber was accessed through a single electronic keypad-locked door. There were no windows and the walls were so thick that electronic signals couldn’t penetrate them to eliminate the possibility of outside surveillance.

The stage was just south of the production offices. It was huge warehouse structure with high perms that were perfect for a soundstage. At the west end was a lower platform with a strange understructure that I looked at for a long time, trying to figure out the purpose of.

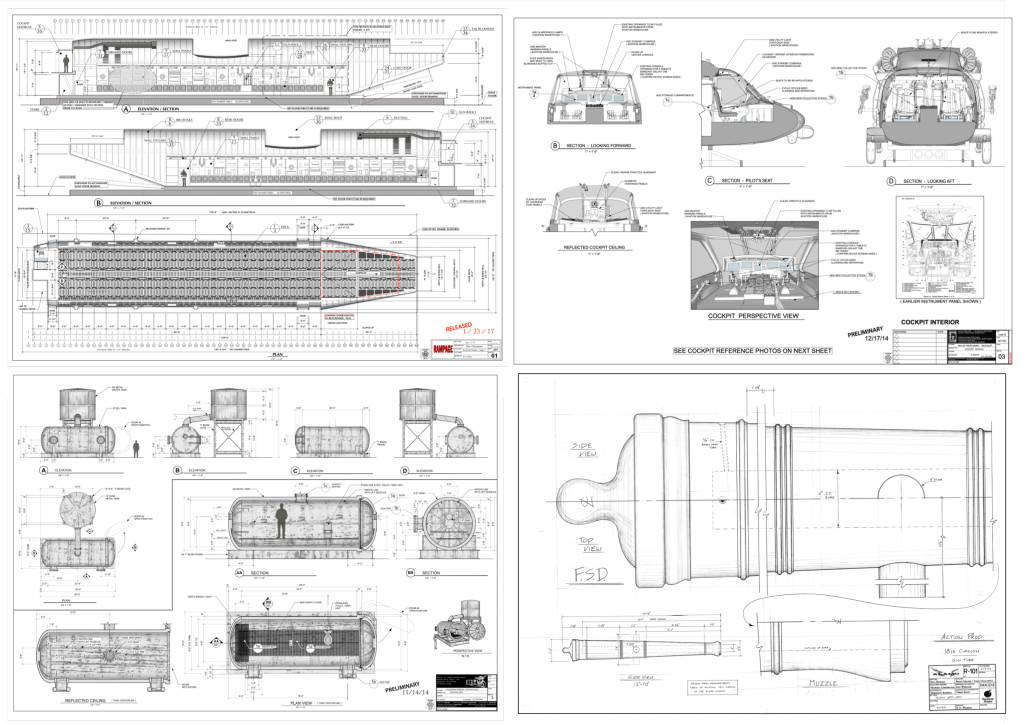

One of the facilities guards finally told me its purpose. I was staring at the underside of the remnants of the simulator for the F-117 fighter plane, the first stealth fighter. He told me that this was where the selected test pilots were brought for their initial trial period.

If they passed the tests in the simulator, they were shipped out to Groom Lake (Area 51) to test fly the actual plane.

There was a large empty room to the west which once held a huge number of computer cabinets that were the ‘brains’ of the simulator.

It was then that I realized that our drawing boards were probably set up in the same area that the Lockheed engineers had been when they designed the first stealth fighters.

Bill told me that shooting a television show there was ironic for him. Years ago he had been suspected of revealing government secrets when he was designing a comedy for William Friedkin. Bill had designed a number of other features for Friedkin including The Exorcist for which he was nominated for an Oscar.

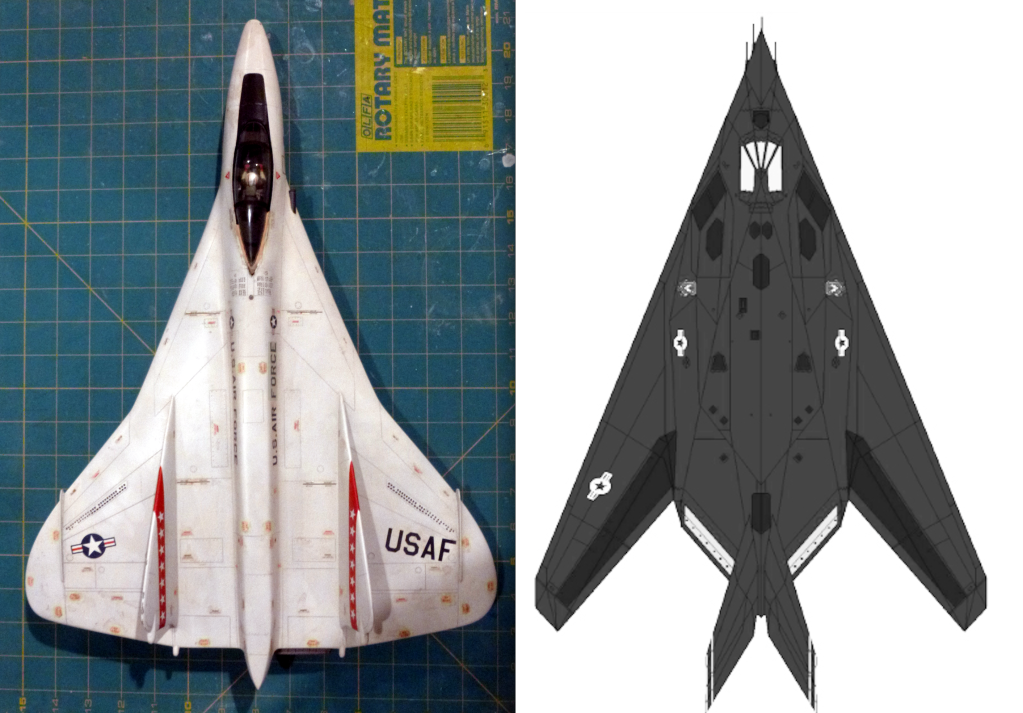

The picture, The Deal Of The Century, was a comedy starring Chevy Chase, about an arms dealer who steals a state-of-the-art fighter plane, the F-19X, from an international air show.

Someone with the government saw the production models of the mockup that they created for the film and told Bill they wanted to talk to him. An Air Force colonel showed up and began to grill him about the planes design. Where did he get the idea for it?

Bill explained that despite the famous cast of characters in the film, the budget largess didn’t extent to the film’s design. As is usual with large productions that feature a lot of well-known actors, the above-the-line talent eats up most of the budget. And what you are left with is the below-the-line limits of a medium budget film.

The colonel insinuated that Bill must have gotten the idea from somewhere, not believing that he had just made it up himself. Bill explained that the budget didn’t allow him do design a completely new kind of plane, so they had taken the basic design from the Russian plane used in the Clint Eastwood film Firefox, and just simplified it. Bill had told the crew to just make it boxier and use flat surfaces rather than the curved surfaces and dihedral of a typical jet.

This would make it easier to create the full-size version that they would most likely have to create for some of the live scenes with actors, as they’d be able to use wood sheet goods rather than other materials to create curved wing surfaces.

The colonel eventually left, convince that what Bill was telling him was the truth.

Bill was baffled until about 1988, when the military introduced the F-177 stealth fighter. The similarities didn’t seem that close to him, but someone who saw his fake plane was concerned that someone had leaked the F-117 design.

Bill didn’t know that those flat surfaces and the twin tails were what had set off warning bells in some government officials mind. The F-117 had been in design since the 1970’s. In the 1960’s a Russian scientist released a paper stating that an objects radar signature was more a matter of its surface structure than its size.

The government started a program called Have Blue, which was a proof-of-concept program to develop a stealth fighter. They discovered that flat surfaces were key to fooling radar waves into producing a small signature. The cement platform at the south side of the property was a test area for measuring the radar signature of different models until a final design was reached that was tested with a full-size mock-up at Groom Lake.

The program would result in the development of the F-117 stealth fighter.

Did anyone know about the fighter program, or the location of the Rye Canyon test site outside of the employees? It seems hard to imagined that someone didn’t at least have an idea that something unusual was going on there. The entire area was patrolled by armed guards 24 hours a day. Even a kid would have known that something must be happening there that was important.

Several months before our company moved in, a fleet of trucks reportedly arrived in the middle of the night. Apparently they were there to recover the remaining files that were stored in the vaults at the main building.

During the production, I found a site where declassified government satellite photos were posted. Among them was a large file of Soviet satellite pictures that the government had recovered from who knows where.

I checked them on the chance I’d find something. And yes, there they were, Soviet satellite photos of the Rye Canyon site. They may not have known exactly what was going on there, but they were sure enough that something important was happening there to allocate satellite attention to the area.

For more photos of the F19X model which was build by legendary model maker Greg Jein see: https://www.therpf.com/forums/threads/f-19x-from-deal-of-the-century-greg-jein-auction-lot.354634

Nigel Phelp’s career began in London where he was studying to be a fine artist. When his school grant ran out, he took a job as a storyboard artist.

Nigel Phelp’s career began in London where he was studying to be a fine artist. When his school grant ran out, he took a job as a storyboard artist.

N.P. – That was really the result of a collective design, The inspiration for that was a picture someone had given me a sculpture of a gorilla. that had been made out of rubber tires, and it was beautiful and expressive, and it occurred to me that that would be the right direction to take for the design of the horse, to take abstract shapes and fashion it from discarded ship parts. It ended up being about 40 feet tall.

N.P. – That was really the result of a collective design, The inspiration for that was a picture someone had given me a sculpture of a gorilla. that had been made out of rubber tires, and it was beautiful and expressive, and it occurred to me that that would be the right direction to take for the design of the horse, to take abstract shapes and fashion it from discarded ship parts. It ended up being about 40 feet tall.