Right now there are empty studio backlots and sound stages all over the world. Most of them are booked, waiting for shooting companies, but entirely unshootable until they are filled with scenery and set dressing. Just in the U.S., over 2 million film personnel sit waiting, wondering when the studio lot gates are going to open again.

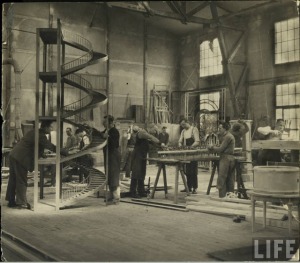

Scenes from studio lots: clockwise from upper left: Melody Ranch; Warner Bros backlot; Sony Studios; Paramount moulding shop; Paramount stage; Warner Bros backlot; Metarie stages, Louisiana.

The studios and production companies wish they could give them a start date.

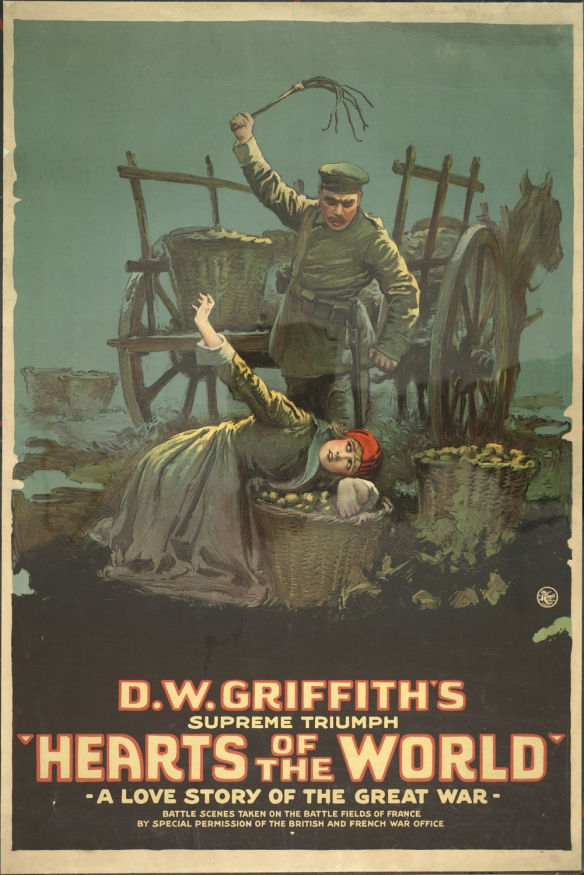

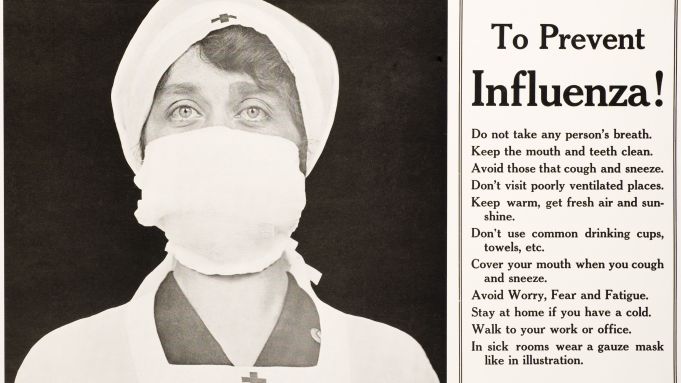

The flu pandemic of 1918 affected the film industry in the U.S. in a way nothing has ever done until today. Some stars died, including Harold Lockwood and Russia’s first film star, Vera Kholodnaya.

Dorothy and Lillian Gish in Orphans of the Storm (Photo by © Hulton-Deutsch Collection/CORBIS/Corbis via Getty Images)

The Gish sisters from Springfield, Ohio, and childhood friend Mary Pickford were spared. A young cartoonist named Walt Disney had forged his birthdate to be able to join the army and drive an ambulance in World War I. He returned from France after the war, possibly bringing the virus with him. He fell sick with the flu but recovered.

Shooting crowd scenes were banned and the studios rushed to finish shooting films before shutting down for a month, some stars decided to forego their salaries so that the movies’ crews could stay employed. It changed everything, including distribution, allowing the studios to grab up the exhibition venues around the country which helped established the studio system.

When the month passed, some of the smaller studios jumped into production before the majors and as a result, were able to attract star talent to their lower budget films. Eager to work, actors jumped at the chance to sign on to films they would normally never have considered. One director said of his all-star cast, “I had the pick of the flock.” Hollywood productions went back to work.

Security guards sprayed people at the gates with disinfectant and people would wear little bags of ground pungent asafetida gum (and very likely olibanum) around their necks to ward off the virus. Olibanum (myrrh) and asafetida are centuries-old elements for calming bees when harvesting their honeycombs. I’m guessing it was an easily obtained substance on studio lots as bee smokers loaded with hot coals and olibanum gum were a common way for special effects men to create smoke on stage sets up into the 1980s. People with long histories in the industry can describe it’s pungent scent from memory. As the pandemic continued to rage, a high death rate from the virus began to be considered as inevitable.

Mary Pickford in a scene from the 1919 film, “Daddy-Long-Legs” (screengrab)

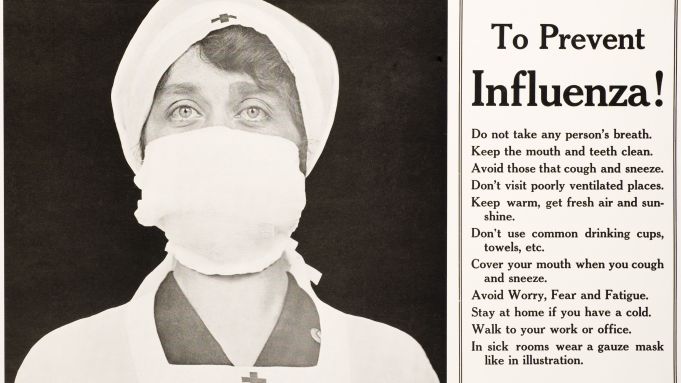

Masks were an accepted accessory, even on camera, having been worked into the storyline of some films. The biggest complaint against them was that they interfered with cigarette smoking. If you pick up a book on the 1918 pandemic you will start to feel that in some ways you are living a real-life version of the movie “Groundhog Day“. Over 50 million people around the world would die. In the U.S., 675,000 people would die, including my great-grandmother.

The COVID-19 pandemic of 2020 may be just as disruptive, if not as lethal.

Living in a surreal world that very few people today ever imagined possible, the networks and streaming services look at their content schedules and carefully note the dates when they are going to run out of new content to air. The onus is now on the studios and networks, both streaming and broadcast, to figure out a solution to the same key problem of restarting production; what classifies as a ‘safe set’?

The news isn’t helpful: The U.S. Government wants to pretend that this will all be a non-issue on May 30, even if it costs lives; A new report states that the coronavirus is exhibiting the ability to mutate at an undetermined rate, sometimes multiple times in a single person; Death tolls in Europe are thought to be higher than reported.

If recent history is an indicator of likely production restarts, namely what happened after both the Writer’s strike of 2007 and the Great Recession of 2008. It was the surge of reality-nonscripted TV shows that filled the void of scripted content; in 2007 because it solved the problems of producing without scripts and in 2008 because it solved the issue of small budgets.

At the Realscreen website, they have posted their first in a series of roundtables of content providers and network execs to talk about the future of the industry. Participants of the first panel were Gena McCarthy, head of programming for Lifetime unscripted, Jodi Flynn, president of Content Group, and Aaron Saidman, president of Industrial Media.

While all three are mainly concerned with unscripted content, the discussion provided a good snapshot of the potential ‘reentry’ plan for the film industry in the States. Two terms that stood out during the roundtable were ‘COVID-proof’ and ‘evergreen’. The networks and streamers are looking for content that will transcend the current pandemic and for shows that will bridge the pandemic-era.

Other content providers have instructed writers to try to avoid COVID-themed stories, pointing out that there are currently more COVID-themed documentaries in development than they think anyone will want to see. There will be a push for more ‘premium-doc’ films and similar shows that have a ‘smaller footprint’.

They all acknowledged that unscripted or reality programs have a definite edge as far as being first in the pipe-line due to the nature of their smaller crews and smaller budgets. They seemed to agree that while budgets will not shrink dramatically in the wake of the pandemic, neither will buyers be willing to provide an open checkbook with the realization that the costs of providing ‘safe sets’ are still a big question mark for everyone.

McCarthy added that Sky Media in Britain has indicated that they don’t see large scale scripted dramas coming back until 2021.

The murmurs coming out of the upper offices hint at some big changes: less travel, more shooting within Los Angeles, less location work and more work within the studios on sound stages and on backlots.

The market is looking for known properties and content that is escapist and aspirational. The networks want shorter schedules, a not-surprising wish considering the challenges of future production.

The advertising market is a big question. Advertisers were cutting back before the pandemic and no one is sure what lies ahead. The Future Of TV Advertising UK just happened in London, where they question the ability of SVODs to compete with streaming channels for ad dollars in an expected post-pandemic recession.

Let’s backtrack, and go back to the Produced By conference held last June at Warner Bros by the Producers Guild. I didn’t want to spring for the $1000 fee to attend but I got the rundown from a producer friend:

22 and 24 episode shows are a thing of the past; The majors are planning to do less big features but spend on bigger budgets; the streamers are planning on creating more content on smaller budgets, generally, meaning the period pieces are going to be a struggle for the Art/Costume/Set Dec/ Prop departments.

And the threat of a Writer’s strike following the contract negotiation fallout hasn’t been resolved, with the writer/agent animosity still lingering in the background.

So what does this mean for the rest of us? When and how are we going to get back to doing what we’re trained to do? Some news articles have hinted that in the wake of production companies piling-on the insurance companies with claims due to the COVID required shutdowns, the insurance companies have said they will no longer recognize COVID claims. The studios are suggesting that crew will be required to sign a form releasing the producers from responsibility in the event of the person contracting the virus while at work.

At first glance, it seems outrageous that they would not take responsibility for an illness, but there is already a precedent. The California Association of Realtors has drawn up release forms that sales agents, home buyers, and home sellers must sign during the selling process absolving them of responsibility in the event of illness. This requires that the parties also wear masks, gloves, and booties during a home tour and only one person from the buyers’ party is allowed to be present. They must stand 6 feet apart and there can be no touching of surfaces. The first viewing of the property must be done remotely through video or digital medium. This is now complicated by the LA council voting to ban in-person showings of houses for lease or sale. Yikes.

In a recent interview, one producer mentioned what I had only heard in passing from other people; the idea of a quarantined show. If you are a Navy veteran you may start to understand what this would mean. Think of a tour on an aircraft carrier, a floating city. Unless the ship stops in a port the only way to get anything on or off that ship is by helicopter or a ship-to-ship transfer.

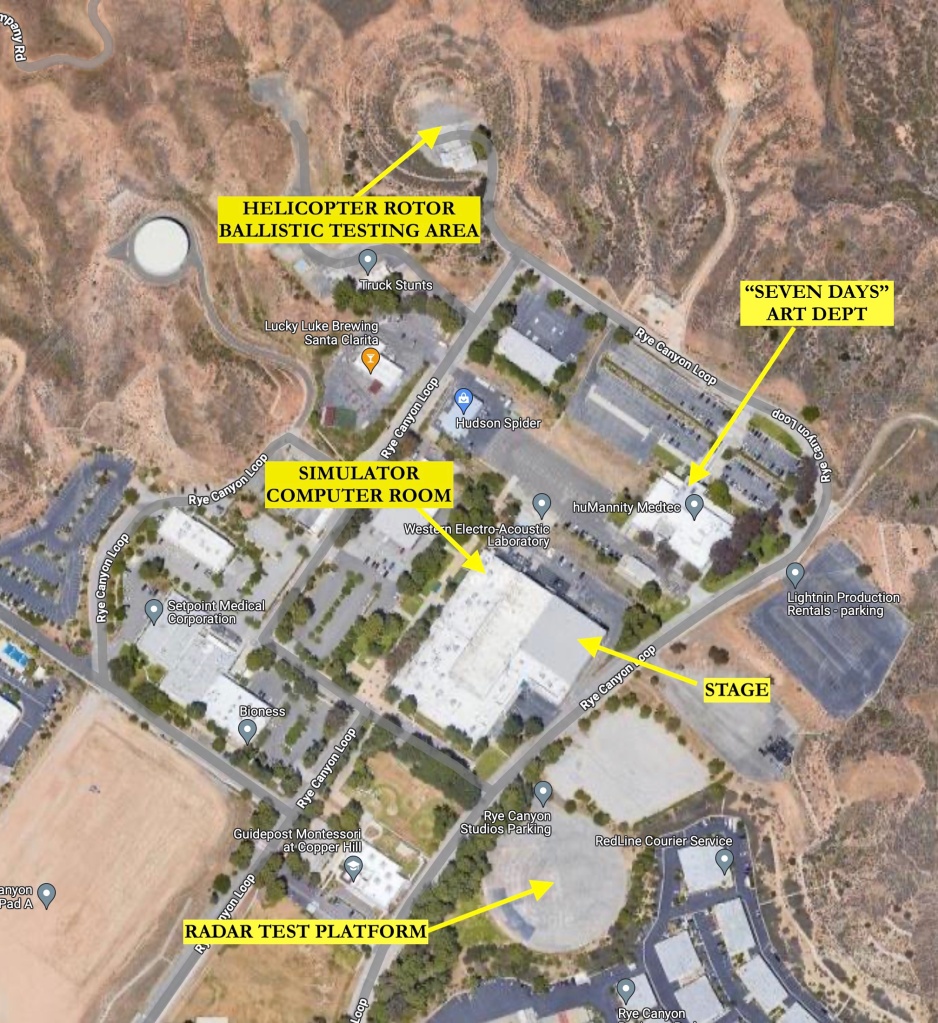

They are talking about testing an entire crew and then sequestering them on a lot or confined location until the end of the shoot. Equipment would have to be cleaned and brought in, a self-contained caterer would be part of the quarantine, no visitors or unnecessary personnel. This might work for most of the shooting company but would be hell for production designers, art directors and set decorators much-less construction crews, painters, set decoration crews and others who need to come and go.

To stay on a reasonable budget there would need to be ample pre-production time, like there used to be, thorough scheduling, shot lists, locked scripts, efficient production schedules. There would be no room for the loose, time-wasting shoots that we often see today with their endless last-minute changes which are usually a product of rushed productions and indecision. This scenario sounds more and more unrealistic.

Kurt Sutter recently mused on this conundrum, saying the quarantine process is much more realistic for a feature than a series. He was dubious of relying on a testing process after his doctor told him many of the tests only have a 48% accuracy rate.

He laid out what he believed was the bottom line: compromise from everyone.

“There are going to be sacrifices made. There are going to be changes that feel like a compromise. I think everyone has to wrap their brain around the fact that they’re going to have to do their job a little bit differently. And if everyone can go into it with that mind-set from top to bottom, I think we can figure out how to do this. I think when we’re going to hit a wall is when people start getting to that point of like, that’s not how I do this, I can’t do my job this way. I think everyone is going to have to figure out how they do their job under these circumstances.

And if they can’t do it that way, then they need to go away. That goes from the creative end — because we’re going to have to make changes in terms of how we write scenes, where we shoot them, and so on — to the directors, who are going to have to compromise visual integrity. Everyone is going to have to go in and say, I can’t have the same expectations I had a year and a half ago. It will be about, how do I do my job under these conditions? And if people can make that adjustment, we can f*cking get through this. If they can’t, we’re not.”

Sutter mentioned that a 40-day quarantine for a shoot would, for him, be a maximum time that you could expect people to be shut away from family and society. What does would this mean for art departments and designers who can often spend 9 months on a picture?

Tyler Perry recently outlined his plan to return his studio in Atlanta to functionality as well.

His studio is the former Ft. McPherson military base and the facilities which the studio includes may be a point of envy to other studios who need to create a crew-quarantine situation. Complete with on-base housing consisting of separate homes as well as barrack-style housing, Perry’s 330-acre studio already has the infrastructure to create such a contained shooting situation.

Materials, including set dressing, would have to be delivered through the main gate and go through a sterilization process like everything else.

Another point in Perry’s favor of having this situation work is that Perry shoots fast, completing an entire season of 22 episodes in 2 1/2 weeks. His plan is to shoot in three-week blocks.

“We will do three weeks at a time, then take a week off so the crew would go home to be with their families. Then they come back, and we start all over again,” he said. “There is another testing process, everybody comes back, we lock down for three weeks while we shoot the next season of the next show.”

With so much riding on the soundness of the quarantine measures taken, and the possible consequences of someone on the crew getting sick, especially a lead actor, the stakes are pretty high. I don’t envy the people who have to come up with the solution, but they have to find one.

Perry was very forthright about the necessity of waivers:

“We are in the beginning of talking to insurers and insurance companies but absolutely, in order to be a part of this you would have to sign some type of release or waiver. Any of this falls apart between now and the next couple of weeks…If one of the union reps says no, if one of the cast says no, I don’t feel comfortable with it, or the insurance carrier says we won’t cover you, then none of this happens. I just thought that this was the best way to get us to work and get things moving. But all of these things have to line up. From the approval of the mayor, to the approval of the CDC, to the approval of Emory Health and Del Rio…all of these things have to line up for that to happen.”

Even Sutter admitted that because the insurance companies will balk at covering a pre-existing condition, some type of waiver will be a given:

“And I think as a result of that, I think everyone’s going to have to sign that f*cking waiver. There are going to be people who don’t want to do that, and I get it. But I do think that if studios want to get productions up and running and they want to get them insured, there’s going to have to be a certain risk/reward that is going with both cast and crew.”

2020 isn’t going to be anything like we thought it would be.

UPDATE: 5/8/2020

An article at the Deadline website covers a preliminary draft of a document put together by The British Film Commission which proposes safety protocols for reopening the film and television industry there. Among the drafts recommendations are for departments, such as construction, set decoration and lighting, to be given extra time to prevent overlapping set work. The paper also proposes:

- Art department crew should be given more time to sanitize props, furniture, and set dressings that come into contact with cast and crew

- The handling of key props should be limited to the relevant actors

- Props and decorations should be purchased online where possible

Further reading:

When Film and TV Production Starts Again, How Will the Crews Stay Safe?

Reopening Hollywood: David & Christina Arquette Lay Out Bold Plan To Open Production In Arkansas & Brave COVID-19 Shutdown

Flu Season: Moving Picture World Reports on Pandemic Influenza, 1918-1919, Richard Koszarski

https://www.archives.gov/exhibits/influenza-epidemic/records-list.html

The Great Influenza, John M. Barry

R.D. Wilkins

Nigel Phelp’s career began in London where he was studying to be a fine artist. When his school grant ran out, he took a job as a storyboard artist.

Nigel Phelp’s career began in London where he was studying to be a fine artist. When his school grant ran out, he took a job as a storyboard artist.

N.P. – That was really the result of a collective design, The inspiration for that was a picture someone had given me a sculpture of a gorilla. that had been made out of rubber tires, and it was beautiful and expressive, and it occurred to me that that would be the right direction to take for the design of the horse, to take abstract shapes and fashion it from discarded ship parts. It ended up being about 40 feet tall.

N.P. – That was really the result of a collective design, The inspiration for that was a picture someone had given me a sculpture of a gorilla. that had been made out of rubber tires, and it was beautiful and expressive, and it occurred to me that that would be the right direction to take for the design of the horse, to take abstract shapes and fashion it from discarded ship parts. It ended up being about 40 feet tall.