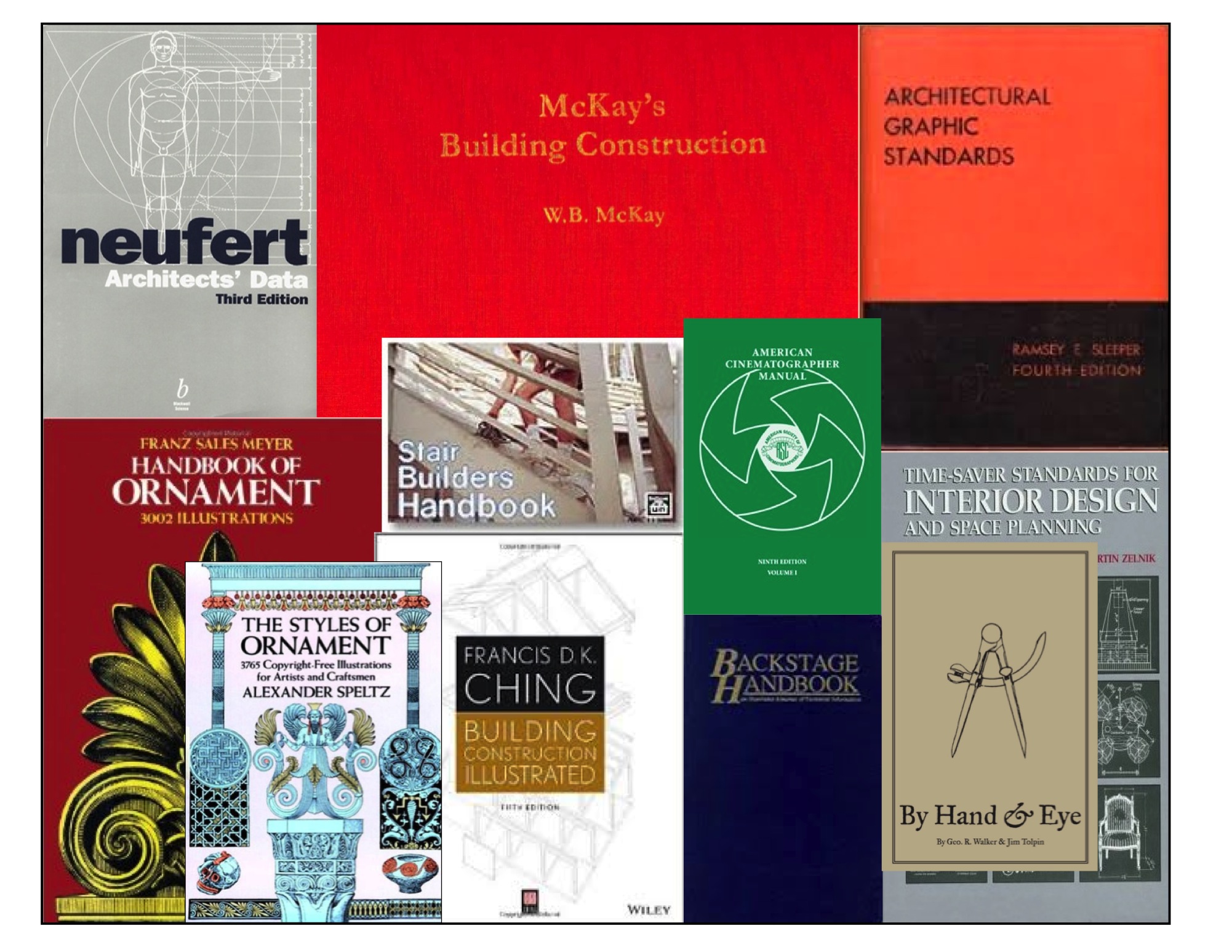

Ten years ago, I wrote a post on 10 design books that I thought everyone should have. Looking at that list now, I think I need to expand on it by adding a few more to the list.

Here is my must-have list with sources:

1. Architectural Graphic Standards – 5th Edition –

This was when the books were filled with great hand drawings and actually showed you in detail how things were built. There are lots of period details as well. Out of print for over 50 years, (at least in this edition) you can still find copies for anywhere from $20 to $200. The 3rd edition would be a suitable replacement. the first edition is also good to have and has been reprinted several times. Check Abebooks for copies. Not available digitally.

If you are in Great Britain, McKays is the closest equivalent, and is actually superior in a number of ways from our standpoint as set designers. On the Continent, an older copy of Neufert’s is a must. See this earlier post for details. Not available digitally.

___

Another option in England is Period House, by Jackson & Day, which goes into extensive detail about common interior architectural elements for restorers. In Germany, the best book on period construction I’ve found is Konstruction Und Form Im Bauen, by Friedrich Hess. There are lots of very nice drawings and measured details. It’s long out of print but you can still find copies second-hand. In Sweden, an excellent book on traditional construction is Stora Boken Om Byggnadsvård, by Göran Gudmundsson. This is a current book and still in print. In Italy, a nice book on traditional construction techniques with detailed drawings is Il Legno e L’arte Di Contruire Mobili e Serramenti. None are available digitally.

***********************************************************************

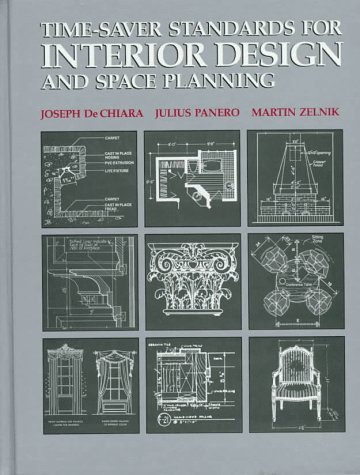

2. Time-Saver Standards for Interior Design and Space Planning, 2nd Edition.

This is the interior design complement to Architectural Graphic Standards and covers nearly every situation regarding building interiors. You can find used copies for around $50. There is a digital version available but it’s not only difficult to navigate because of the size of the book but at the price you’d be better off getting a hardback edition.

Another companion to this is a nice slim book that is for kitchen and bathroom standards in the U.S. The NKBA Kitchen & Bathroom Planning Guide was created to make common building codes and layouts available to designers in an easy to use format.

*********************************************************************

3. Styles Of Ornament – Alexander Speltz.

Originally published in 1904, this book uses over 4000 drawings to illustrate 6000 years of historical design. As a general design reference I don’t think it has an equal. Architecture, furniture, text, carving, metalwork are all covered. A must-have. About $20 new.

The Handbook Of Ornament by Franz Meyer would be a close second. Available from a number of publishers for as little as $10. A digital version is available.

Low Budget Option- download the online PDF here.

******************************************************************

4. The Stair Builder’s Handbook – T.W. Love –

Not a design book, but a book of rise-and-run tables that make stair layout a breeze. Available from various sources for about $20.

Low Budget Option – download the PDF Common Sense Stairbuilding and Hand-railing. Skip the mind bending section on handrail layout and skip to page 99. Also, Stair building, which has a nice section on ornamental ironwork.

*******************************************************************

5. Backstage Handbook – Paul Carter.

Originally a technical manual for theatrical designers, the book is full of great information for film work as well. There are more details in this earlier post from several years ago. It is one of the most widely used books on stagecraft in the U.S. Available from Broadway Press for about $22. No digital version is available.

********************************************************************

6. Building Construction Illustrated – Francis Ching.

An excellent and thorough book about construction details including wood framing systems and masonry. About $46.

Low Budget Option – access the online PDF here of the 4th edition.

********************************************************************

7. The Classical Orders of Architecture – Robert Chitham

I think this is the best modern book around that deals with the classical architecture proportional system. This book was out of print for quite a while and fortunately is back in print. The new edition deals with the proportions for both metric and Imperial systems. Copies can be found for about $55.

Low Budget Option – Get the PDF of American Vignola by William Ware and The Five Orders by Vignola.

*********************************************************

8. Illustrated Dictionary of Historical Architecture – Cyril Harris

With over 5000 terms and 2000 line drawings, this book covers architectural history from the ancient period to 20th century Modernism. Along with the European styles, it covers Japanese, Chinese, Indian, Islamic and Mesoamerican styles. About $35 from various sources.

Another classic book in a similar vein is A History of Architecture On The Comparative Method, by Sir Banister Fletcher. This dense, fully-illustrated book covers the time periods from ancient times to the 20th century, focusing on Western culture. It was the most widely used general architecture reference book for decades.

Used copies are easy to find for around $20. A good scanned copy of the 1905 edition can be found in PDF form here for download. Avoid reprints. Most of them are badly scanned from originals and the fine details of the illustrations is lost. A 20th edition has been published in two volumes that comes in at over 1600 pages and includes new sections on cultural architecture from countries not fully represented in the original edition. This runs at around $250.

******************************************************************

9. Elements Of Style – Edited by Stephen Calloway

This has been a standard Art Department reference manual for quite some time. Subtitles as “a practical encyclopedia of interior architectural details”, the book covers the periods from 1485 to modern day. Each chapter covers a different time period and is separated into thirteen sections which each feature an interior element, making it easy to cross reference similar elements from other time periods. The book includes over 3000 drawings and 1300 photographs to accompany the written analysis. In hardcover for around $75. Used editions can be found for as little as $20.

******************************************************************

10. By Hand & Eye – George R. Walker & Jim Tolpin.

If you’re just starting out in set design this is one of the first books I’d tell you to buy. Bad proportions can ruin a design. This book will give you a solid understanding of proportion and keep you from making simple mistakes. You can download a sample chapter here. Also, I wrote a longer post on the book earlier. Walker and Tolpin are promising a workbook that will come out later this year based on the book’s concepts so look for that. Available from Lost Art Press for $51, hardbound. A PDF is available for $24.

*******************************************************************

11. Principles Of Design – William Varnum

This is a recent reprint of a book published in 1916 under the title Industrial Arts Design. The book lays out the basics of design, with step-by-step rules for designing not just furniture but pottery and metalwork as well, with sections on enriching a surface with detail or hardware. The rules translate easily to architectural forms and will seem like obvious, common-sense choices once you are exposed to them. This hardback edition is the second run of a limited printing. By Lost Art Press at their website. Hard cover edition is $41.

*****************************************************************

12. Human Dimension & Interior Space – Panero & Zelnik

This book explains the science of anthropometrics, which is the study of human body measurements on a comparative basis. Whether you are designing interior elements, furniture, or vehicles, this book will help you create those spaces with easy to read diagrams and charts that detail the huge disparity in shapes, sizes, and capabilities of the human form. The authors warn against designing for a ‘standard size’ human body which in fact, does not exist. New in hardcover at about $24. Digital versions are also available.

*****************************************************************

13. Field Guide To American Houses – Virginia Savage McAlester

Described as the “definitive guide to identifying and understanding American domestic architecture”, this book is considered an essential source for understanding the myriad of styles and elements that define American houses. With over 1000 drawings and photographs, the book separates the various styles into chronological categories and explains the details and accents that define each of them with clear, simple sketches. The second edition is about $24 in paperback.

****************************************************************

14. Illustrated Cabinetmaking – Bill Hylton

I covered this book in detail in an earlier post. One reviewer referred to this book as the Gray’s Anatomy of woodworking, and that’s a pretty accurate description. If you’re going to design furniture you need to understand how it’s built, and this book explains it with over 1300 color illustrations and exploded views of 90 different pieces of furniture from different time periods. There are sections on joinery, standard dimensions, and sources for construction drawings. Paperback editions are about $24. Digital editions are also available.

***************************************************************

15. The Encyclopedia Of Wood – Aidan Walker, Editor

There are numerous books on tree identification but this one stands out to me because of the variety of wood that it covers and the large, clear color photographs of each of 150 species grain patterns and figure. There are also chapters on how wood is processed, what wood movement is, and how veneers and lumber are milled. In paperback for about $35.

***************************************************************

16. American Cinematographers Manual – American Society of Cinematographers

The new 11th edition will cost you about $120 in hardback and almost the same in it’s digital version through the iTunes and Android sites. Earlier used editions can be purchased for a third of the price of a new edition, but much of the latest technology isn’t in them. This is the go-to book for all things dealing with cameras and image capture. A lot of people will tell you you don’t need this. I’m sure you might also have a great career as a car designer without knowing anything about how cars work. Because when it comes down to it, all we’re really doing is designing big, pretty things to bounce light off of. Just remember, if the department names were based on physics we’d be the Light Reflector Design Department.

*************************************************************

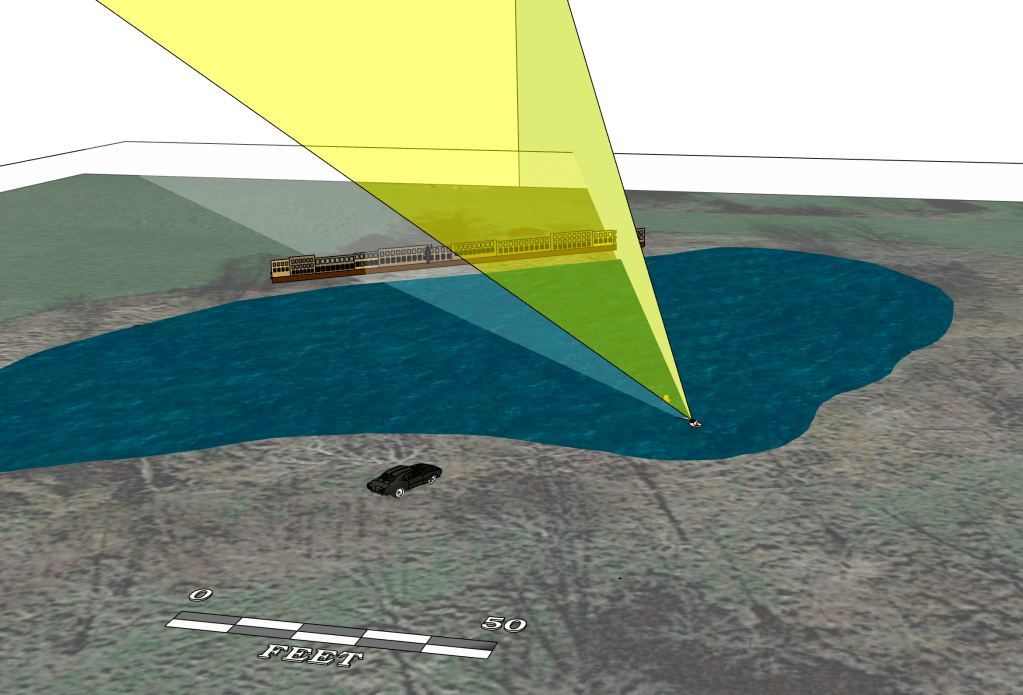

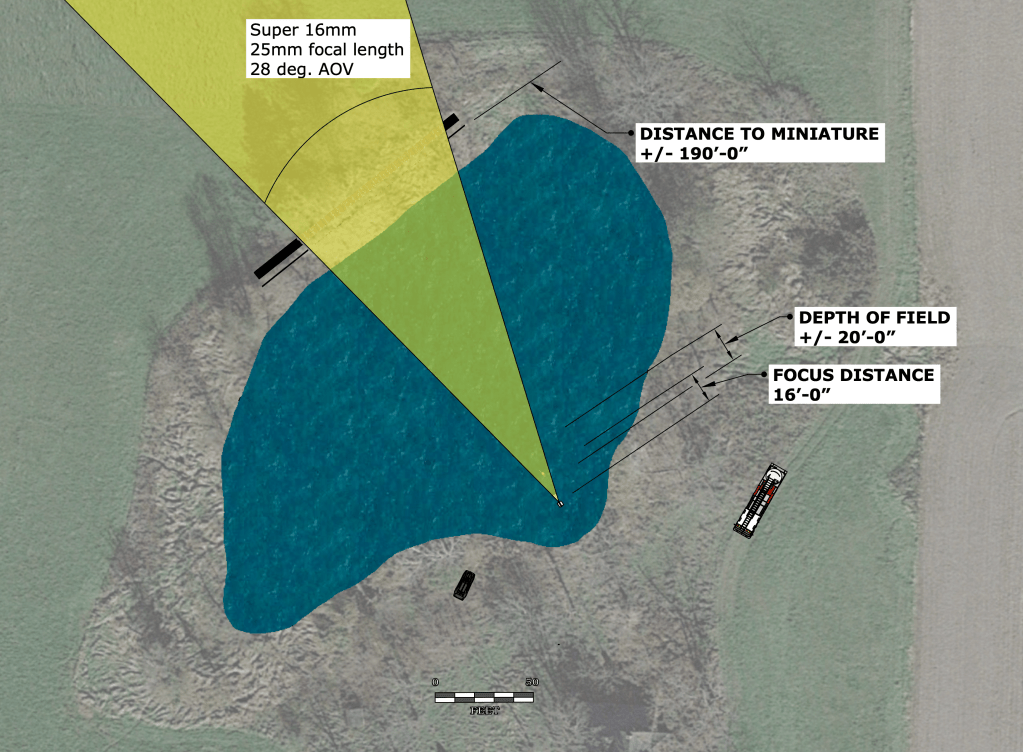

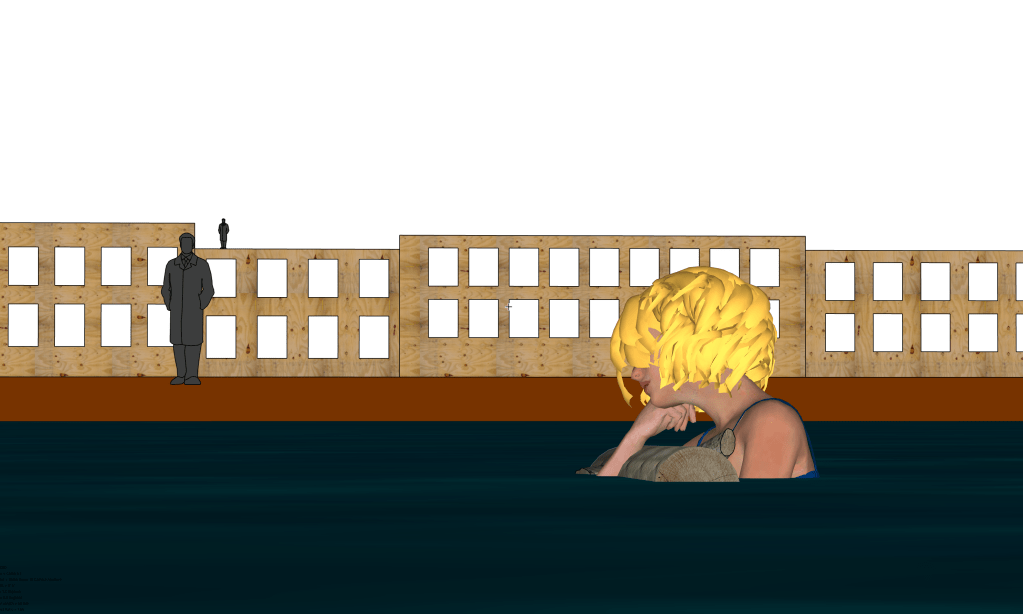

17. The VES Handbook Of Visual Effects – Okun & Zwerman, Editors

Published by the Visual Effects Society, this +1000 page book covers every type of visual effects shot you will encounter. From in-camera effects like miniatures and mechanical effects to green screen work, motion-tracking, LIDAR, tracking shots, LED wall stages, and everything in between. It’s the most complete book on visual effects that has been produced so far. Consider it to be a complementary reference to the American Cinematographers Manual. In paperback, the new third edition costs about $65.

***************************************************************

18. Chenier’s Practical Math Dictionary – Norman Chenier

This book is an odd duck in many ways but it has been a real time saver on a lot of occasions. There are sections on descriptive geometry, survey and layout techniques, solutions to common math problems, and other information that you’ll struggle to find anywhere else. In paperback, the latest edition is $26.

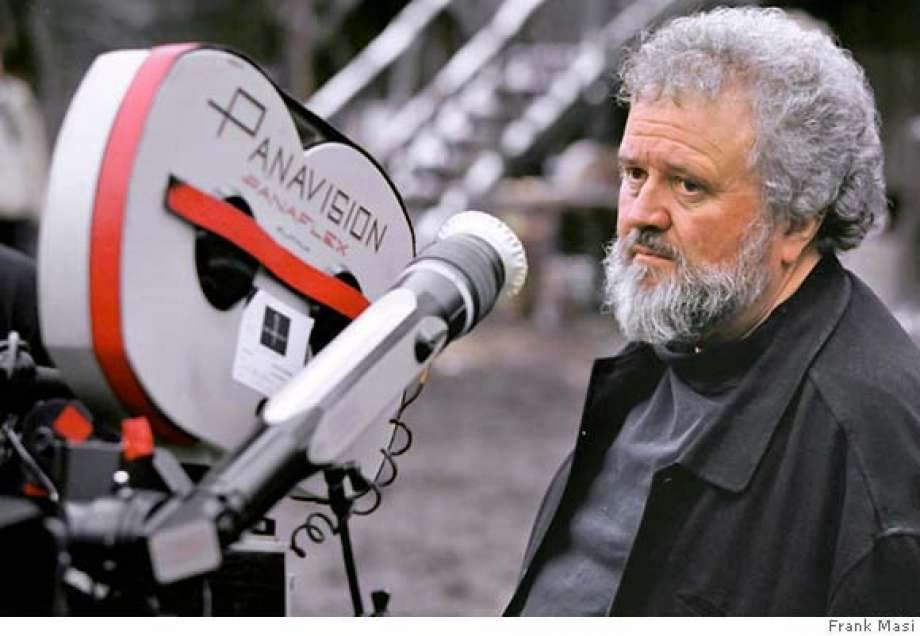

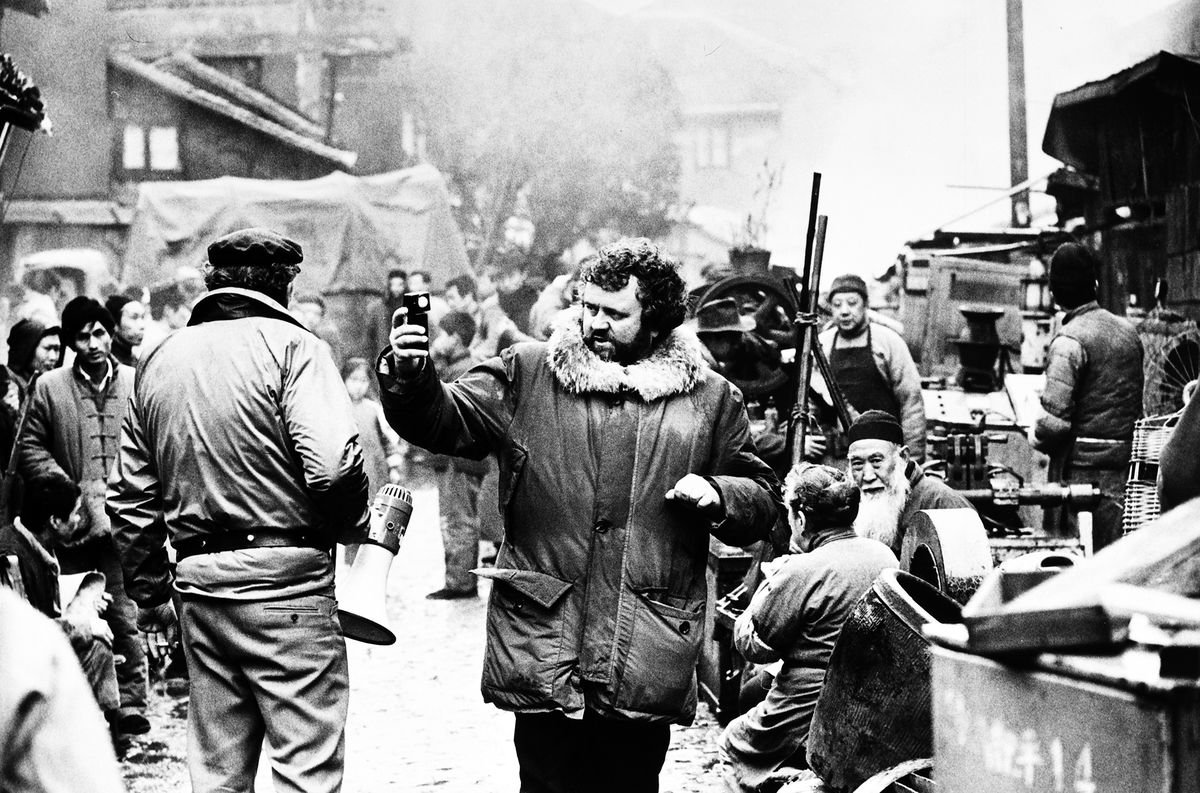

Allen Daviau, the five-time Academy Award-nominated cinematographer of films such as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Empire Of The Sun, Avalon, Bugsy, and The Color Purple, passed away on Wednesday from complications of COVID-19. In 2007 he was given a Lifetime Achievement award by the American Society Of Cinematographers.

Allen Daviau, the five-time Academy Award-nominated cinematographer of films such as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Empire Of The Sun, Avalon, Bugsy, and The Color Purple, passed away on Wednesday from complications of COVID-19. In 2007 he was given a Lifetime Achievement award by the American Society Of Cinematographers.