The latest story to excite below-the-line crew members in Los Angeles is the news that Ben Affleck and Matt Damon have made a deal with Netflix for their new film, The Rip. The contract includes a stipulation that provides for a bonus to the entire crew of the production if the show performs well on the streaming platform when it is released.

This one-time bonus would be in addition to the salaries which crew members were paid during the production.

Affleck told an interviewer at the Toronto Sun, “We wanted to codify a model that included 1,200 people on the crew, as well as the cast, because we firmly believe that when everyone is investing themselves, that makes it likelier that you’re going to have something that people connect to more.”

“How this business survives and thrives going forward, we believe, is going to be fundamentally related to the fact that (filmmaking) really is a collaborative art form, so (we are) seeking to incentivize all of those folks into making the best movie possible.”

Wether this idea can be a part of other contracts at other production companies and what it’s outcome for the crew will be remains to be seen.

The idea is a revolutionary first for large-scale Hollywood studio productions, but it’s an idea that isn’t a new one. The idea had been suggested to major studio executives 40 years ago by British producer Sir David Puttnam, and it didn’t go over well.

In 1985, I was a Fellow in the Directing Program at the American Film Institute. AFI was a choice place to be and it was a heady experience, especially at that time. It was a time before the internet, or DVDs with director and producer commentaries, or an endless variety of interviews and how-tos by professional filmmakers.

It’s a place where major directors and producers will show up to screen and talk about their latest productions with the school’s community. We had visits from David Lean, Steven Spielberg, John Hughes, and others . Nearly every week there was another Hollywood luminary who none of us would have met in person if not for the AFI program.

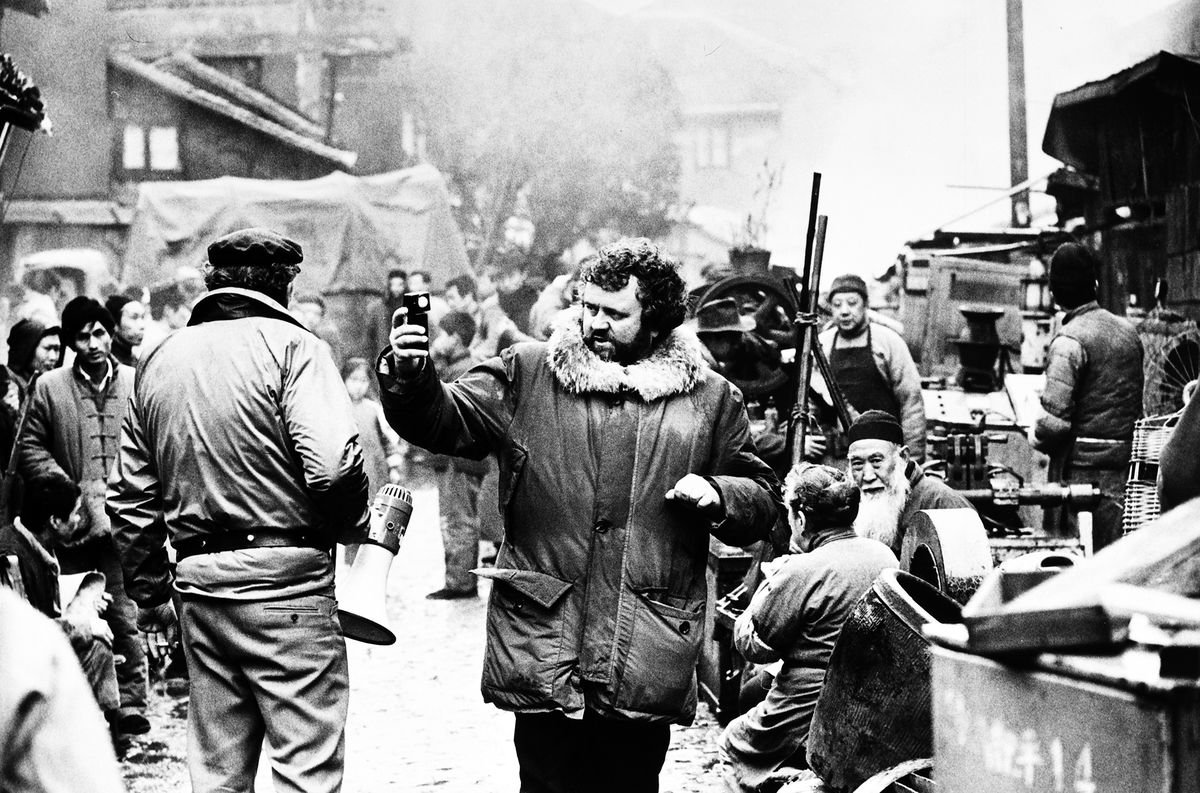

One week it was announced that the guest artist would be Oscar winning Producer David Puttnam. And, he would be guest lecturing not just for the day but for the entire week. He would be screening his new film, The Killing Fields, which was nominated for five Oscars.

Also that week, he screened three of his other films; Midnight Express, Chariots Of Fire, and Local Hero. It was a whole week of master film classes by the man who had produced them. I wish they had been recorded.

Sir David was incredibly cordial, approachable, and even self-deprecating at times. He told us that when he was producing his first film, in an effort to prove he was on top of the goings-on of the production, he would go over the budget expenditures for each week. One week he caught a suspicious cost difference and called the line producer into his office.

The line producer looked confused when Puttnam pointed to the line item listed as Focus Puller. “How would this same equipment cost a different amount every week?” he asked. He said his moment of satifaction at having rooted out financial irresponsibility quickly turned to embarrasement when the man told him that the ‘Focus Puller’ was the title of a crew position, not a piece of equipment.

He was as generous with information as he was with his time. As we watched the films he would interject stories about the production challenges they had faced, both comical and daunting. He would examine a production from nuts to bolts and would barter with a director over, for instance, how many animals they actually needed in the background for a believable scene.

Very down to earth in his presentation style, he entertained us with stories of his current meetings with studio leadership. He was being courted at the time by a studio to take over as head of the operation. They were as surprised by his attitudes toward the current Hollywood system as he was by the studios’ expectations and business plans.

They showed him various options for homes in Los Angeles, all with huge properties and large pools and they told him about the options he could have as a company car. He said he didn’t want a house with a pool and that the cars they were suggesting were ridiculously large.

He had already ruffled feather among a number of studio heads and other producers with some of his comments about the Hollywood system, which he considered to be a “me-too” attitude, as he thought that the system seemed to be content with just copying other people’s successful films.

“You can’t do creative work in an environment like that”, he told an interviewer from Time Magazine. In one communication to Columbia’s corporate owners, Coca Cola, he said, “The medium is too powerful […] to be left solely to the tyranny of the box office”.

He also pointed out his disgust at huge actor salaries. A New York Times article stated later, “What surprised and dismayed him most about Hollywood was the amateurishness.”

Once he was installed as the new studio head at Columbia, he made it clear that he wanted to make films he would be proud of. “I would be shattered if I could not look with pride at Columbia’s pictures. That would not be true of 75% of films made in Hollywood today”, he said. The New York Times also reported that he was “enough of a realist to want to make entertaining movies, and enough of an idealist to want his films to have social value.”

He wasn’t afraid to point out mistakes that he felt had been made in what were considered audience favorites. A writer for The Hollywood Reporter in 2016 wrote that “He had slammed the ending of the blockbuster E.T. The Extra Terrestrial because he thought the alien should have stayed dead.”

On some days he would express his ideas for revitalizing the entire studio production process including changing the pay structure that was in place in Hollywood. He wanted to move some of the profits down to the people who actually made the films. He had talked to a number of individuals about a possible system where a crew member could benefit from the film’s actual profits, choosing between taking a full salary or partial salary and points on the film’s box office.He said they looked at him as if he was mad.

Sir David would take over at Columbia Pictures in September of 1986. He would stay on as head of the studio for just 13 months. After his tenure, when asked about by a writer at The Hollywood Reporter, he said “Looking back, I was a good movie producer who made the mistake of being persuaded I could run a studio. I hated almost every day of it.”

On the last day of the week that he spent with us at AFI, he didn’t rush off as you would have expected of most people of his stature. When the lecture ended, he stuck around for small-talk. A group of us lined up to say goodbye and offer our thanks for the one-of-a-kind week of instruction and advice.

I hung out toward the back, not sure of what I’d say as a proper thank you. I approached him and he displayed a big smile and held out his hand. I thanked him and then, in a prescient, self-interested moment, I blurted out my unexpected question.

“Is it true?” I asked him. “Is the industry as hard on relationships as some say it is?”

His smile faded a little and he looked at me with a kind of empathy. “Yes”, he said. “It definitely can be.”

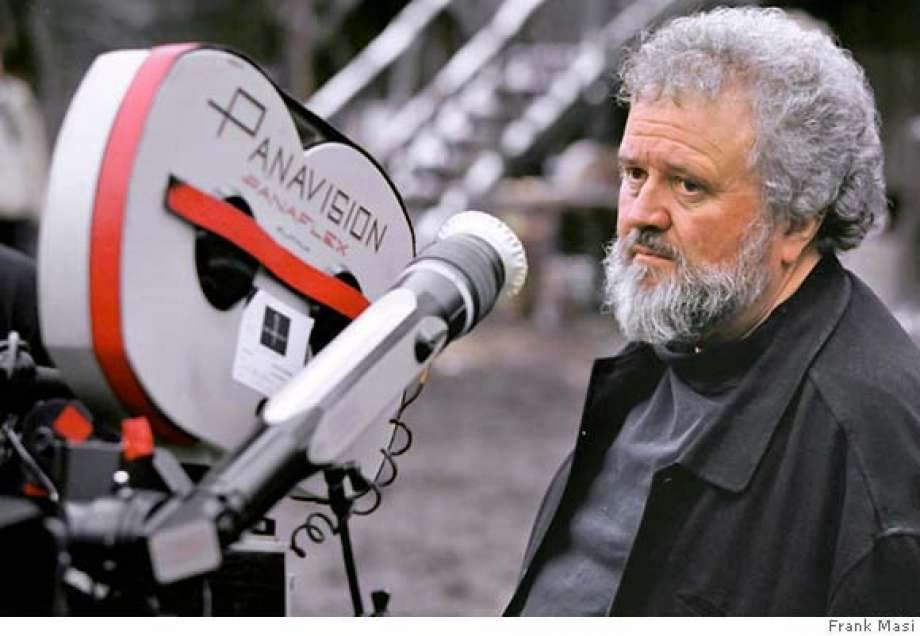

Allen Daviau, the five-time Academy Award-nominated cinematographer of films such as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Empire Of The Sun, Avalon, Bugsy, and The Color Purple, passed away on Wednesday from complications of COVID-19. In 2007 he was given a Lifetime Achievement award by the American Society Of Cinematographers.

Allen Daviau, the five-time Academy Award-nominated cinematographer of films such as E.T. The Extra-Terrestrial, Empire Of The Sun, Avalon, Bugsy, and The Color Purple, passed away on Wednesday from complications of COVID-19. In 2007 he was given a Lifetime Achievement award by the American Society Of Cinematographers.