Here are three high-tech to no-tech ways to calculate the height of a building or tree or pole or anything else you need to know the size of but can’t determine with a tape measure.

1. Theodolite Pro

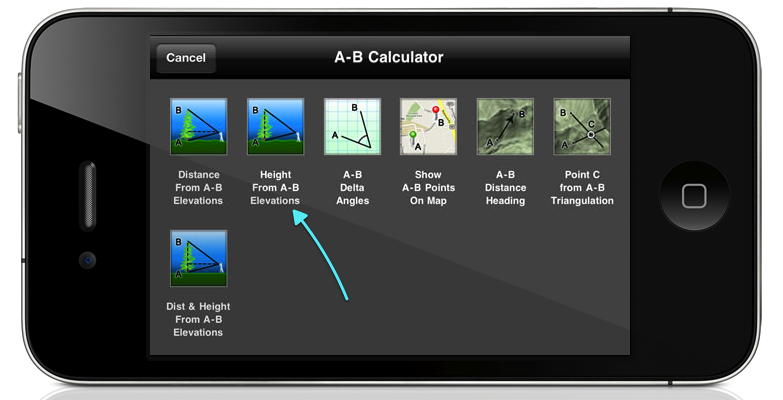

Theodolite Pro is an app for the iPhone, iPod Touch and the iPad. Made by Hunter Research & Technology , it’s a multi-function augmented-reality app that combines a compass, GPS, digital map, zoom camera, rangefinder, and two-axis inclinometer. Theodolite overlays real time information about position, altitude, bearing, range, and inclination on the iPhone’s live camera image, like an electronic viewfinder.

At $9.99, it’s worth more than 4 times the price.

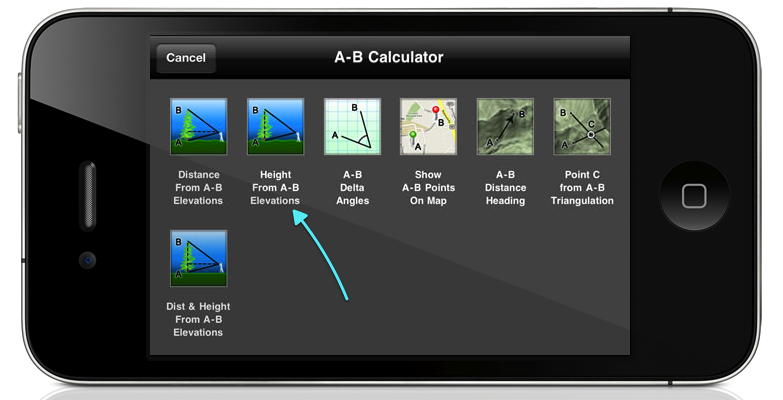

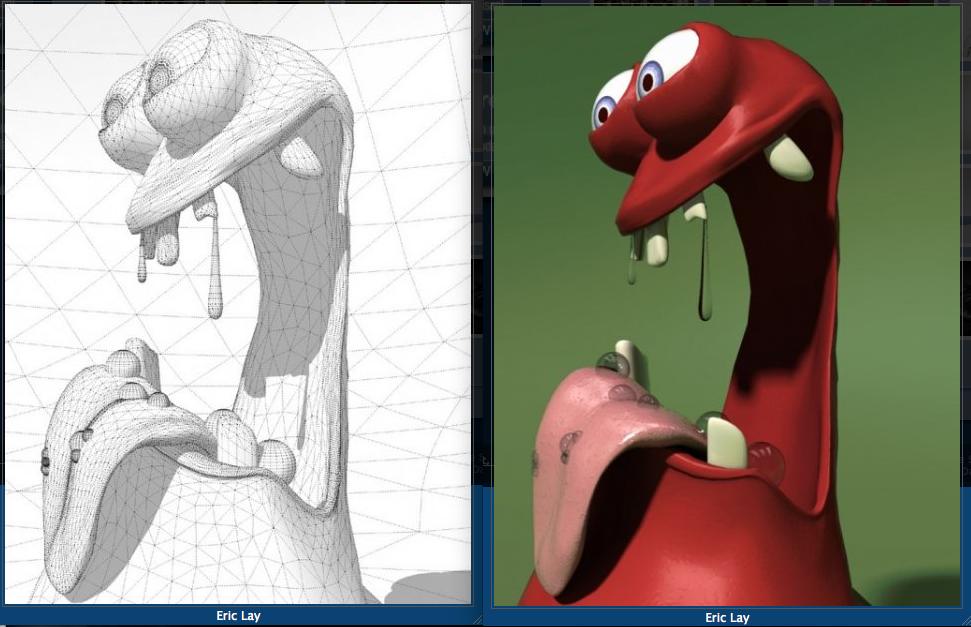

Theodolite Pro screen

The apps screen data gives you your position in either latitude and longitude or UTM units, as well as the time and date and your elevation. On each side are the horizontal and vertical indicators in tenths of a degree. The device has a one-button calibration function as well as a 2x and 4x magnification for pin-pointing a particular object. There are several options for the center crosshairs, one of them are a pair of multicolored floating boxes which merge and turn white when you are plumb in both directions.

You’ll get a much better result if you mount the device on a tripod. For an iPhone, the method I like is with a Snap Mount. It has 1/4″ female sockets for mounting in either a vertical or horizontal direction.

Snap Mount device for the iPhone 4

Once the phone is mounted, you point the center at the top of the object and push the “A” buttton to take a reading. Then tilt the device toward the bottom of the object and take the “B” reading.

Then the app will ask you for your distance to the object. The more accurate your answer the more accurate the result will be. So, you’ll either have to pace off your position or measure the distance with a reel tape or laser measure device.

If this isn’t possible, you can use the option to determine the distance and height, although this will probably not be as accurate.

There is also an optical rangefinder built into the view screen that works by way of a series of concentric circles in either size factors or mils, that you can use to determine distance if you already know the size of an object in the foreground.

optical rangefinder rings

This app has been a best-selling navigational app for some time and has become a very useful tool in many different fields. You’ll find it’s very useful when doing field surveys and it’s certainly a lot cheaper than an analog theodolite.

2. Clinometer

A clinometer, or inclinometer is a device which measures the angle of slope and uses basic trigonometry for estimating height. My clinometer is a combination clinometer and optical compass made by the Finnish company Suunto and is called the Suunto Tandem. Like the iPhone, you’ll get better results if it’s mounted to a tripod and the Suunto has a 1/4″ socket for this.

The Suunto Tandem

You look through the peep sight, leaving both eyes open. The graduated scale is superimposed over the object you’re centered on and you can read the results as either a percentage of slope or degrees of elevation.

You sight the top of the object in the device and read out the angle. Then you refer to the cosine table on the back of the device. From there it’s just a simple trig calculation. Adding the height from the ground to the center of the clinometer will give you a very close figure for the objects height. Like before you need to know your distance from the object you’re measuring, so it would be a good idea to determine your average stride to have a semi-accurate way of pacing off distance when surveying.

You sight the top of the object in the device and read out the angle. Then you refer to the cosine table on the back of the device. From there it’s just a simple trig calculation. Adding the height from the ground to the center of the clinometer will give you a very close figure for the objects height. Like before you need to know your distance from the object you’re measuring, so it would be a good idea to determine your average stride to have a semi-accurate way of pacing off distance when surveying.

The back of the Tandem has tables of cosines and cotangents printed on it to make calculations easy.

The list price of the Tandem isn’t cheap, but I’ve seen them go for $20 on Ebay, so you should check there before you buy a new one. The results may not be quite as accurate as with the Theodolite app, but you’ll never have to worry about a dead battery and the device will still work perfectly 50 years from now. Like the Theodolite app, it’s good for shooting grades and taking elevation surveys as well.

A handy addition to both the above devices is to get a Keson Pocket Rod. It’s a collapsable surveyors stadia that rolls into it’s case. It has black and white graduated scales on one side and red and white on the other. It’s a great tool to have to put in location survey photographs as well for accurately scaling details from photos when you don’t have time to measure everything at a location. They come in both Imperial and metric units.

Keson Pocket Rod

3. Biltmore Stick

This is the cheapest and easiest method of determining height but it’s also the least accurate. This is a trick I learned from my Boy Scout days. It’s based on the Biltmore Cruiser stick which is a way of determining the heights and widths of trees and how much lumber they would yield. The Biltmore Stick ( sometimes called a hypsometer ) gets it’s name from the famed Biltmore Estate in Asheville, North Carolina and was invented in the 1890’s by a German forester named Carl Schenk who was the master forester at the estate.

A real Biltmore stick has graduated markings that take into account for foreshortening but there’s a less expensive method. We were taught to use a yard stick (not very compact) or a 6 foot folding rule, which is a little wobbly to hold vertically. I like to use a Four Fold rule which is the original folding rule from the mid 19th century. They were sometimes called Blindman’s rules because the numbers are large and easy to read, making them perfect for this use. Garrett Wade carries a good reproduction of them. They fold down to just 9 inches long and fit nicely in a survey bag.

The way to use this one is to pace off 25 feet from the tree, building, etc. Turn and face it, holding the rule at arm’s length. 25 inches from your eye is the ideal distance. hold the rule so that the bottom of it lines up with the bottom of the object, like so:

using the Four Fold rule as a Biltmore stick

Read off the number than lines up with the top of the object and that will give you the height in feet. If the object is above the 25 inch mark, back up another 25 feet and multiply the results by 2. If it is still above the 25 inch mark, back up to 75 feet away and multiply the results by 3, and so on.

This method won’t necessarily give you a really accurate height, but it will give you a number that will be pretty close, say within 3% to 4% of the true measurement, providing you are very close in the distance increment and the rule is very close to 25 inches from your eye.